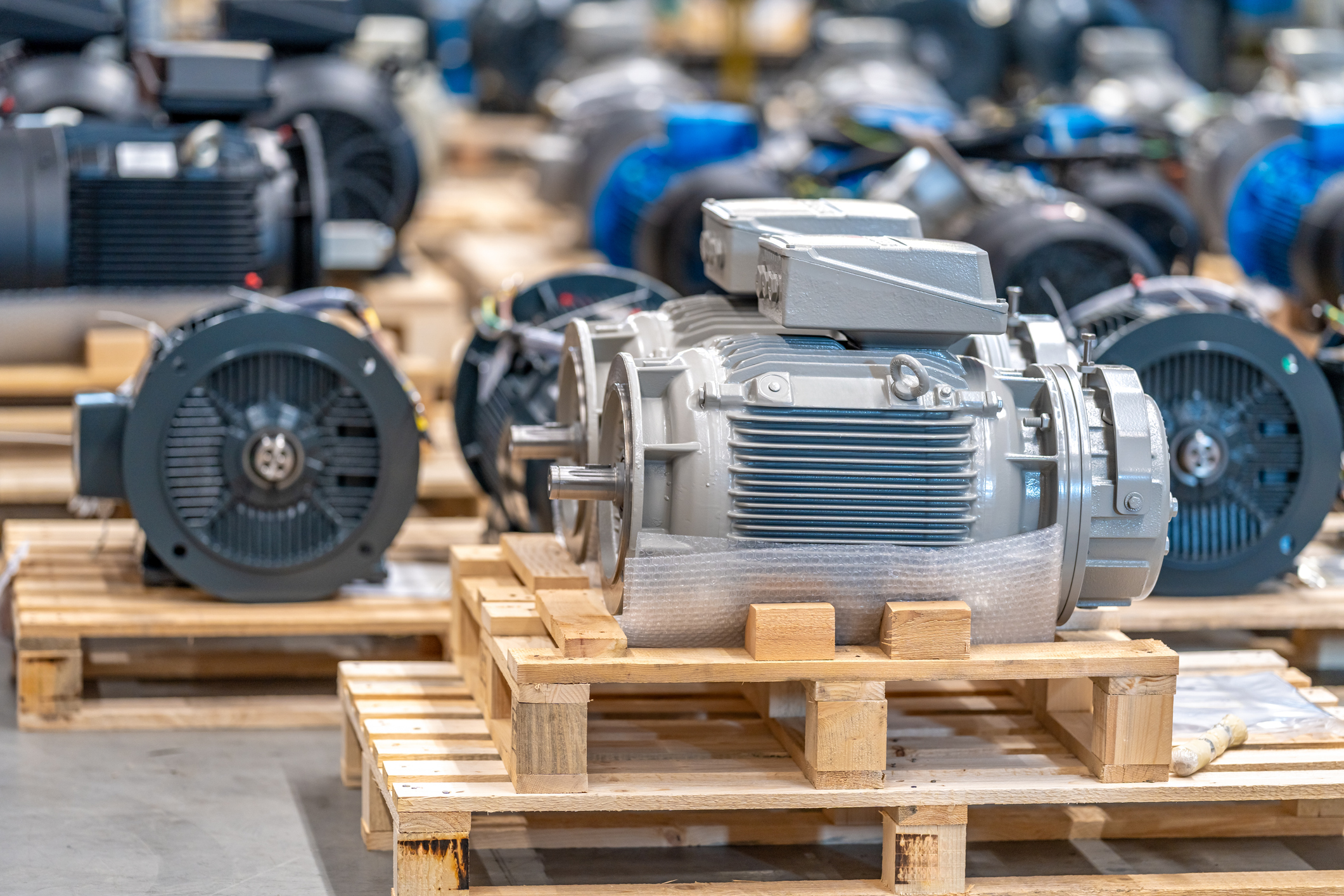

Electric Motors

by Diane M. Calabrese | Published December 2025

Does it hum, whir, or spin? Then “it” likely has an electric motor.

Electric motors keep devices—and their components—moving. The hush that comes over a home or workplace when there’s a grid-level power failure signals motors that were keeping refrigerators cold, desktops cool, and buildings ventilated have stopped.

True battery backup and generators (gas, diesel, and solar) may take over, but even the switch will probably be noticed. Why would we notice? We are inured to the sounds emanating from the motors in our life, including traffic, and thus instinctively notice when the sounds disappear or change.

In just about every setting, an abrupt change in sound—including motors powering equipment on jobsites—indicates a problem. A problem that should not be ignored, however inconvenient.

Many parties have vested interest in promoting understanding of electric motors. Among them are manufacturers of the motors, motor repair technicians, makers of equipment that incorporates electric motors, the U.S. Department of Energy (Energy.gov), and environmental groups promoting clean energy.

As such, the parties make available a huge amount of information easily found in the digital world and, of course, quickly collected and aggregated by AI searchers. Let’s approach it all a bit differently to start, and then return to some of the best basic resources for those wanting to learn more, resources that happen to be at Energy.gov.

Pete Gustin is a product manager for Comet/HPP with Valley Industries–Comet Pumps in Paynesville, MN. He kindly answers a few fundamental questions regarding the relation of electric motors to equipment.

Pete Gustin Responds

Cleaner Times (CT): Which are the essentials that you wish every power-washing contractor knew/understood about an electric motor?

Gustin: That there are way fewer moving parts, and an industrial-grade electric motor will outlast a gas engine by a long shot.

That the comparison between electric and gas is very seldom apples to apples. An electric motor allows for so many dynamic behaviors that can save energy, costs, materials, etc. It is very important to do a proper analysis with a professional to truly understand the cost savings and dynamic opportunities that an electric system can provide.

That the normal limitations of 120-volt systems don’t exist when using a hybrid AC/DC motor. With these motors, a battery can act as a buffer so that amperage limitations are much, much higher, albeit for a limited amount of time.

CT: In the course of the workday, a power-washing contractor encounters/relies upon perhaps many electric motors. Which among the possible motors encountered is most interesting or concerning to you and why? [We note that home and day-beginning tools, such as a Braun electric toothbrush, have an electric motor, and welcome comments beyond the worksite—e.g. a vehicle.]

Gustin: The most interesting category of electric motors going forward will be battery-powered motors between 1.5 and 5 hp. This power range will experience a revolution over the next few years, and the days of gas engines in this range are numbered. Batteries have reached high capacities, and the cost and size are both shrinking exponentially. Almost every manufacturer of power equipment in this range is considering all battery-powered options.

CT: Concerns about the meaning attached to “motor” range from emphatic concern (motors are electric and engines are combustion) to no concern at all. If you would like to comment on the dichotomy, please do.

Gustin: Electric motors are cleaner and quieter. They require less maintenance and present less risk of fire if designed properly, and they offer enormous returns on investment. Look for financing options and government incentives to overcome the hurdle of upfront costs that contractors and homeowners face in converting to battery electric. And study the comparisons carefully as battery-powered machines offer hundreds of advantages in equipment design, work hours, mounting options, RPM adjustments, etc.

Resources

In deftly handling our question about the difference between electric motors and internal combustion engines, Gustin reminds us of the many important comparisons that deserve to be made between electric motors and gas engines.

(Note: We understand the serious concern some members of our industry have about using the term motor for an internal combustion engine [ICE]. But we will not delve into it here except to acknowledge that many thoughtful people consider the term “electric motor” redundant because motor should not be used to label an internal combustion engine.)

The Energy.gov website is an excellent starting point for members of our industry who want to learn more about motors. Technical publications, tip sheets, case studies, and energy assessment tools regarding motors can be perused by title and linked to instantly. The offerings from the energy department include an energy assessment tool.

For example, an older (2014) Tech Brief from the energy department provides an excellent introduction to the reasons motors fail. See “Why do motors fail?” (https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/04/f15/tech_brief_motors.pdf).

Here are the basics of what the brief just cited tells us. Motors fail because of heat, power supply anomalies, humidity, contaminants, improper lubrication, and unusual mechanical loads.

The heat that leads to failure can be produced by overloading, frequent starts, high ambient temperature, low or unbalanced voltage, high-altitude operation, and inadequate ventilation. Temperatures that exceed the range for optimal performance can cause problems in multiple ways, such as contributing to the deterioration of insulation and changing the consistency of lubricants, leading to bearing failure.

There are voltage variations in the electricity supplied by the grid. Power companies strive to keep them in a narrow range, but if a significant voltage imbalance occurs (more than one percent), it can cause problems for a motor.

With grid suppliers being expected to interface with renewable (home) generation from solar and wind, voltage fluctuations are not unusual. A voltage regulator is a good idea, even though it may only be needed occasionally.

The technical brief goes into much more detail on each of the banes to a motor. And it’s a good instructional tool to use directly or as a template for training purposes. A more succinct—and more basic still—resource comes from the Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Advanced Manufacturing Office at the Department of Energy. It is Motor Systems Tip Sheet #3 titled “Motor Systems.”

See the motor systems tip sheet via (https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/04/f15/extend_motor_operlife_motor_systemts3.pdf). The tip that’s emphasized at the onset concerns the longevity of a motor. The more carefully a motor’s owner follows a maintenance schedule, the longer the motor will last. The caveat is that in harsh environments motors will deliver fewer hours of service before they must be replaced or refurbished.

According to the tip sheet, bearing failures, which can be precipitated by a harsh environment, account for two-thirds of motor failures. This is where responding quickly to changes in a familiar sound can prevent a motor from incurring damage that cannot be repaired.

If something seems to be unusual about a motor—a new sound, an unexpected wobble—check out what’s going on. Vibration often signals trouble.

NEMA [National Electrical Manufacturers Association] establishes the standards for protecting motors. It sets the limits for ambient temperature, voltage variation, frequency of starts, etc. The limits, which will be conveyed with the motor, should not be exceeded.

Electric motors are daily fixtures for members of our industry. They power pumps, compressors, vehicles, fans, and drills.

Obviously electric motors can provide power in environments where safety would be compromised by a combustion engine. In parking garages, using a diesel-powered pressure washer with insufficient ventilation is hazardous.

Ventilation through partially open garage walls—and augmented by fans—is not enough. Contractors opt to run long hoses from washers running outside the garage to avoid risk of exposure to elevated carbon monoxide levels, but the longer hoses dimmish efficiency of the job.

The potency of combustion engines—higher energy output per unit of fuel—is attractive, but the interest in finding ways to switch more functions to electric motors continues to grow.

Continuous improvement in direct current (DC) motors, such as brushless DC motors, is allowing for longer service and greater efficiency. (As a nice aside, many notice the lower noise level with brushless DC motors.)

The types of electric motors go well beyond the simple AC versus DC divide. But that divide is generally the first subdivision made. Because rectifiers can be deployed to change AC to DC and then feed a device as a battery would, the division gets murky right from the start.

General subdivisions for AC motors are induction (asynchronous) and synchronous. General subdivisions for DC motors are brush, as well as brushless, and stepper [moving in discrete steps rather than a continuous rotation].

Stepper motors may be either DC brushless, or DC achieved through a rectifier. A stepper yields precision in movement in rotation and angularity. The stepper is a crucial player in medical applications and in robotics.

Longer life accrues to electric motors compared to combustion engines, thanks to fewer parts. But as controls (see stepper motors) are added, the number of parts requiring attention may increase. And there are still situations—long distance from the grid, too much power required, etc.—in which electric motors will not be a match for the application.